For years, she had trained to get to this time and place. All that Christine Sinsky, MD, had learned and all the technique she had acquired would be rigorously and passionately applied to do better, be faster. She set her sights on the end. Now to make it across the line.

Rising out of the waters of Lake Monona in Madison, Wisconsin, after swimming 2.4 miles on a warmer-than-you’d-like September morning, Dr. Sinsky runs to the changing area to start the 112-mile bicycling leg of the grueling, gargantuan Ironman triathlon. Break through that leg and all that remains is the trifling matter of a 26-mile marathon.

But something is off.

Dr. Sinsky—the 59-year-old internist, the AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction and one of the nation’s leading lights in the transformation of medical practice to prevent physician burnout—is having trouble seeing out of one eye.

Is the lens of her sunglass smeared? Is it just a residual artifact of the swimming goggles that Dr. Sinsky had cinched extra tight to keep out water during the swim? No. It is an amigrainous migraine. She gets a few migraines each year, though it has never happened during a race before.

With impaired vision, Dr. Sinsky cycles for 75 miles as her arms become increasingly tremulous with fatigue. What do you do when you cannot see the way forward? What is the right way to proceed when you have lost the feeling for the path ahead?

Dr. Sinsky, ever attendant to benefits and risks, concludes that it would be imprudent to continue given the course ahead.

“Can’t see. Can’t hold the handlebars. Dangerous downhills to come? Better stop,” she says, looking back on the ill-fated 2016 race that is registered with those three ugly letters: DNF—did not finish.

But to those who know and admire Dr. Sinsky, it would come as no surprise that the next September she was back in Madison for another go at the Ironman. They will tell you about her exacting zeal—the animating spirit that keeps her looking for new, more efficient and less burdensome means of achieving the desired outcome: to take the next step, to finish the race, to move medicine forward.

Making residency and family a match

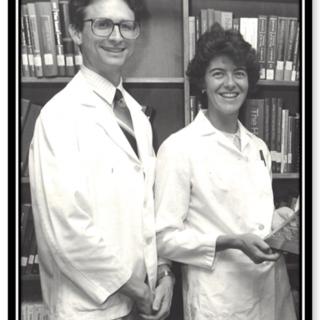

That is what she has been doing since the days she trained for another awesome task—practicing primary care in the dysfunctional U.S. health system. Dr. Sinsky and her husband, Thomas Sinsky, MD, met in ballroom dance class as undergraduates at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. They fell in love. She was a year ahead of him, and Tom followed Christine to UW’s medical school.

Then they landed residency spots in the internal medicine residency program at Gundersen Medical Foundation in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

The Sinskys also started their family during residency, and the beginning of their family also marked the start of the Sinskys’ career-long track record of refusing to let their medical vocation impede their calling to raise and be present with their children.

As they were both in residency during in the early 1980s, well before duty-hour limits, how could they possibly manage children without having them cared for nearly around the clock by others? Unlike many other resident couples in which the nonphysician partner shoulders the child-rearing and household loads, that wasn’t an option for the Sinskys.

It’s said that necessity is the mother of invention. Here, motherhood was the source of the invention.

Rather than compromising their family or career goals, the Sinskys proposed an innovative solution to their dilemma to their program director. They would share one residency spot. After the birth of each of their two children—Carolyn, then David—Christine took six months off. Then Tom, in turn, would take time off so that Christine could return for the next block of residency.

So that was the idea. But would the program director, a former military physician, go for it? The Sinskys went to him and proposed what Dr. Christine Sinsky describes as “a novel, but workable idea,” and waited for his response.

“He did not blink an eye,” Dr. Christine Sinsky says of the man, Col. Edwin Overholt, MD. “He said, ‘No problem. We can do that.’” It turned out, fortuitously, that another couple had made a similar arrangement years prior, but the Sinskys did not know that.

As the Sinskys finished residency within six months of each other, they found their practice home with Medical Associates Clinic in Dubuque, Iowa. The group, which has more than 170 physicians and other advance-practice providers, is Iowa’s oldest multispecialty group practice.

The physician-owned group “empowers the physicians to have a certain amount of control over the details of their daily work,” Dr. Christine Sinsky says. So less than a year out of residency, she was on the lookout for better ways of doing things.

The first transformative steps

“Within that first year, we started getting labs done ahead of the appointment, because we realized that if we had the results we had a more meaningful visit with the patients and less chaos in the practice, and less likelihood of missing an abnormal test result,” Dr. Christine Sinsky says. The move also saves tens of thousands of dollars a year in physician and staff time.

Also during those first few years in practice, Dr. Sinsky implemented the idea “to renew all the patients’ stable chronic illness medications at the annual appointment.” The flexibility within Medical Associates Clinic allowed her to experiment with that. The change was made within the Sinsky practice “as opposed to having to get every physician in the department or every physician in the clinic to agree to do a process the same,” Dr. Christine Sinsky says.

This and many other of Dr. Christine Sinsky’s efforts would become the core of the AMA STEPS Forward™ collection of open-access CME modules that offer innovative strategies allowing physicians and their staff to thrive in the new health care environment.

When most time-squeezed primary care physicians struggle to tread water amid the increasing bureaucratization of practice, Dr. Sinsky took the initiative to find practical ways that met the quadruple aim of better patient experience, better population health and lower overall costs with improved professional satisfaction.

“I just didn’t know any better,” she says. “Maybe I’m just optimistic that you can always make things better.”

Dr. Tom Sinsky agrees, noting: “My wife’s an incredibly efficient person. She has the mind of an engineer. She hates to see any moment wasted.” Yet the clarion call of family also was a major factor.

“We had two young children and we were both tied to medical practice, taking call, doing clinic and working weekends, so we were up against the wall,” he says. “Someone has to cook dinner. We couldn’t spend the extra two to three hours in the office and get work done.”

Work that matters

Dr. Christine Sinsky remembers the glorious fall colors in 1994, seven years after the Sinsky practice came into being. The leaves had turned rusty red, with little yellow underbellies. And then, turning away from her office’s wall-to-wall window with a view of the Mississippi River, she felt trapped. There would be no romps in the leaves with the children while the sun hung in the sky.

She still had a stack of charts to go trudge through, and that would take at least another hour.

“If I’m going to stay in practice, I have to do something differently,” she thought to herself. “I have just become a documentation drone.”

It was around this time that in their practice the Sinskys “started to systematize all the standardized, predictable work of the practice and shared work with the nursing staff,” she says. “So the nurses could be the ones to close all the care gaps. They could be the ones who gave all the immunizations during rooming, as opposed to waiting for me to remember that—among all the other things going on with the patient.

“All the changes we made in our practice came out of a similar impulse to maximize the enjoyment of the work, and doing work that mattered, and work that the nonphysicians on our team could not do,” Dr. Christine Sinsky says.

Dr. Tom Sinsky puts a different spin on the practice transformation at play.

He imagines many primary care physicians—including himself, to a certain degree—as akin to soldiers fighting in trench warfare.

“Never put your head up, try to get through, and get home,” he says. Dr. Christine Sinsky has the wherewithal to “look up, look past the snipers and say, ‘This doesn’t make any sense. We’ve got to change this,’” he says. She “could somehow get this view from the top, looking down from some observation point to see these dysfunctional systems and patterns.”

He notes, in particular, the impact of expanding the nurse-to-physician ratio (5-to-2) in the practice and giving nurses an expanded role in rooming patients, carrying out standing orders and taking charge of tasks such as EHR data entry, and medication reconciliation.

“We spend quality time with the patient,” Dr. Tom Sinsky says of the physician’s role in the Sinsky practice. “I don’t take the computer in the room. My nurse has a computer.”

Deb Althaus joined the Sinsky practice in 1997 and served as the primary nurse until Dr. Tom Sinsky retired from practice earlier this year. At that time, Dr. Christine Sinsky also decided to retire from clinical practice to spend 100% of her working time in her VP role at the AMA.

“As we transitioned to team-based care, they called me the quarterback of the team,” Althaus says. She would triage incoming phone calls from patients, pharmacies, other clinics and other offices. As much of this communication became centered in electronic systems, Dr. Christine Sinsky worked with Althaus and the other nurses on staff to better manage the EHR in-basket.

“We had protocols that we’d work under and we set guidelines” on matters such as abnormal laboratory values, Althaus says. She estimates that of the 50 to 100 EHR inbox messages that came in daily, only about 10% needed Dr. Sinsky’s attention.

Departing from Dubuque

Word started to spread within Medical Associates Clinic about the practice transformation afoot in the Sinsky practice, says Brian Sullivan, MD, chair of the group’s internal medicine department.

“When other physicians would get frustrated with certain facets of their practice, they’d say, ‘How are Tom and Chris dealing with it? Because they’ve probably already figured it out,’” Dr. Sullivan says.

“They’ve been tremendously giving and open with sharing their ideas,” he adds, noting that the Sinskys played an influential role within months of his arrival at Medical Associates Clinic from residency.

“It’s hard to overstate their impact because it’s been there since I first came here 20 years ago. Even when I started really making customized adjustments to my practice, it was all influenced by what they were doing.”

But Dr. Sinsky thought these transformative ideas should go beyond Dubuque. She began taking on speaking engagements at medical conferences to talk about the improvements that she, Tom and the rest of the team had accomplished together. She also started working with mentors such as University of California, San Francisco Family Medicine Professor Thomas Bodenheimer, MD, MPH, American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation President and CEO Richard J. Baron, MD, and Harvard Associate Professor of Medicine John D. Goodson, MD.

A recent search of the National Library of Medicine’s website reveals that Dr. Sinsky has written or co-written more than 50 peer-reviewed medical journal articles, often in high-impact outlets that reach broad swaths of practicing physicians and physician influencers.

Michael Tutty, PhD, brought Dr. Sinsky to the AMA, where he is group vice president of physician satisfaction and practice sustainability.

“Chris Sinsky has become one of the foremost experts in the areas of physician dissatisfaction, physician burnout and joy in medicine,” Tutty says. “There are a lot of people talking about these issues and selling themselves on it for a profit. What we do here at the AMA has academic rigor, and Chris took this role because she really believes in the work, and that this was a platform at the AMA to make a difference in physicians’ lives. It’s not just lip service.”

Aside from her essential role in bringing the influential STEPS Forward modules to fruition, writing and speaking engagements, Dr. Sinsky oversees the AMA’s work on organizational assessment of physician burnout, and measurement surrounding the efficacy of practice interventions.

Last year, the AMA piloted its work in this area, which includes customized surveys that can help organizational leaders set priorities for changes that can have the most impact on the quality of physicians’ working lives. In 2019, Tutty says, the AMA has repeat customers and is looking to quadruple the number of health systems the Association works with.

The STEPS Forward modules are replete with case studies of how the ideas that Dr. Sinsky put into place in Dubuque have affected physicians, health professionals and patients around the country. To take just one example, six months after an AMA visit to Crusader Health in Rockford, Illinois, that focused on synchronized prescription renewal, a physician assistant reported that “he was saving about 30 minutes a day, his inbox was empty by the end of the day and he was leaving work on time.”

Over the course of a year, that adds up to two solid weeks in time saved. In total, the nonprofit with 70 physicians and other clinicians will save hundreds of hours of clinician time each month. Hours are precious. They can be spent following the fall colors, enjoying a home-cooked meal with family, cutting up the dance floor with the love of your life—or training for a triathlon.

The Ironwoman arrives

It’s another warm September day in Madison for the Ironman event, a year since Dr. Christine Sinsky was forced off her bike by a migraine and arm fatigue. Naturally, she returned to training with new handlebars for her bicycle to address the arm fatigue that helped push her out 365 days earlier. The so-called aerobars serve as arm rests, cantilevering out over the front wheel, allowing Dr. Sinsky to cut the pressure on her hands and wrists.

The migraine does not recur. Dr. Sinsky completes the swim and the bike portions of the competition. Yet even with 23 miles of the marathon behind her, she still is not certain she can make it to the finish.

But she does not waste a stride. She sets one foot in front of the other and soon enough she is in sight of the Wisconsin State Capitol and the finish line, a mere 15 hours and 30-odd minutes after she started slicing her arms through the water of Lake Monona. Her finish time will be good enough to give Dr. Sinsky fourth place in her age group.

Staring in Dr. Sinsky’s direction as she races down Madison’s State Street—out west to Iowa and across the country—is a 7-foot-tall bronze statue. This female figure, draped in robes and clutching the American flag, her hair pulled back, surges ahead with a look of determination etched upon her russet physiognomy.

The figure’s arm is held aloft, offering an encouraging wave toward a future filled with transformative progress. The statue is named after the Wisconsin state motto, but the folks around Madison have come up with their own term of endearment for this bold woman perpetually on the move.

They call her “Lady Forward.”

Redesigning practice—step by step

The AMA STEPS Forward™ collection of practice-improvement CME modules offer innovative strategies that allow physicians and their staff to thrive in the new health care environment. The courses can help prevent physician burnout, create the organizational foundation for joy in medicine, create a strong team culture and improve practice efficiency.

The modules below are among the many modules written or co-written by Dr. Christine Sinsky:

- “Pre-Visit Laboratory Testing: Save Time and Improve Care.”

- “Annual Prescription Renewal: Save Time and Improve Medication Adherence.”

- “Expanded Rooming and Discharge Protocols: Streamline Your Patient Visit Workflow.”

- “EHR In-Basket Restructuring for Improved Efficiency: Efficiently manage your in-basket to provide better, more timely patient care.”

- “Team Documentation: Improve Efficiency, Workflow, and Patient Care.”