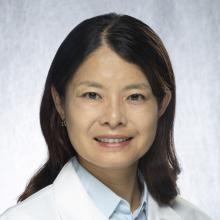

As a resident physician, are you thinking about where you want to build your future in medicine? Meet Yuka Kodama Tsukahara, MD, PhD, IOC Dip.SP.Med, a family and nonsurgical sports medicine physician in Iowa City with University of Iowa (UI) Health Care, and a featured voice in the AMA’s “Finding My Place in Medicine” series.

In this series, physicians reflect on what influenced their personal decisions when choosing where to work—and what they wish they had known earlier. Explore Dr. Tsukahara’s journey to help guide your own path toward a fulfilling medical career.

If you are looking for your first physician job after residency, get your cheat sheet now from the AMA. In addition, the AMA Transitioning to Practice series has guidance and resources on deciding where to practice, negotiating an employment contract, managing work-life balance, and other essential tips about starting in practice—including in private practice.

“Following” Dr. Yuka Kodama Tsukahara

Specialty: Family medicine with a focus on nonsurgical sports medicine.

Practice setting: Health system.

Employment type: Employed by the UI Health Care in Iowa City. University of Iowa Health Care is part of the AMA Health System Member Program, which provides enterprise solutions to equip leadership, physicians and care teams with resources to help drive the future of medicine.

Years in practice: 16.

Key factors that led me to choose to work at University of Iowa Health Care: I’ve only been here about 10 months, but one of the biggest strengths of the University of Iowa is the number and variety of athletes. That opens up a lot of research opportunities, which I’m excited about. My research is focused on female and youth athletes, particularly in the areas of bone health and injury prevention.

Also, the level of diversity of athletes in the U.S. is unique and a real strength. I was the lead physician for the Tokyo Olympics in 2020, and I enjoyed being able to provide health care to such a diverse group of athletes.

What stood out to me during the interview and hiring process: Jeffrey Quinlan, MD, chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine, offered me a Zoom interview, then invited me to Iowa for an in-person interview two years ago. It took a while to make the move because my husband is a neurologist, and I didn’t want to disrupt his career. We waited until there was an opportunity at UI Health Care for both of us.

How feedback from peers and mentors influenced my evaluation process: I met several UI Health Care colleagues, Andy Peterson, MD, and Britt Marcussen, MD, after I was selected as an international fellow by the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM), which is the largest nonsurgical sports medicine organization in the U.S. Dr. Peterson learned I was looking for a job in the U.S. and that’s when he reached out to Dr. Marcussen and Dr. Quinlan, which eventually led me to Iowa.

Why I chose to work in this practice setting: Research is an important part of my work, so I’ve always been more focused on working at university-based health care settings.

The top three qualities for a great place to work: Great colleagues. Dr. Quinlan and Korey Kennelty, PharmD, MS, PhD, the vice chair for research in our family medicine department, have been wonderful. Having supportive people around really matters.

Nice patients. Honestly, that makes a big difference. People are really nice in Iowa, and I’m really grateful for that.

A great place to raise children. It’s incredibly important to me how happy my children are here. My 8-year-old son says he never wants to go back to Japan because he started playing ice hockey here. It’s hard to play hockey in Japan since it’s not very popular. Iowa isn’t a major hockey state, but he plays at the mall rink and is on the local junior hockey team. My daughter, who is 6, is a track athlete. She recently placed second in a statewide meet. They’re both really enjoying it here.

How my current practice supports physician well-being and work-life balance: I didn’t have work-life balance before, so the difference is night and day. It’s not even comparable.

The biggest challenges I faced when transitioning from residency to practice: I was originally trained in orthopaedic surgery in Japan, so I’m board-certified in orthopaedics. In 2016, I shifted to nonsurgical sports medicine, with a focus on treating female athletes.

The number of patients we see in Japan is intense. For example, in the outpatient clinic—including post-op patients—I would see around 150 patients a day. Honestly, it’s not ideal, but you just ... stop smiling.

I wish I had been more prepared for how emotionally tough it would be to see athletes in pain, even when surgeries go well, such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstructions. Recovery is painful and stressful.

What I would have done differently when choosing my first job: I published a paper during the COVID-19 public health emergency on gender bias in sports medicine in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. The findings really highlight how difficult it is to be a female sports medicine physician.

Your judgment gets questioned a lot, even when you’re doing a great job. Even outside the OR, like at sporting events, I’d be there with a younger male physician, and people would call him “Dr. Smith” and call me just “Yuka.” That kind of thing happens a lot. The problem isn’t just with orthopaedics, but it’s more pronounced in that specialty.

How I knew I was ready for a change in my career: Seeing athletes suffer was something I couldn’t tolerate. That’s one of the reasons I became more interested in injury prevention rather than treatment. Fixing injuries is important but preventing them is even better.

How my current role compares with what I imagined: I’m really happy with my transition to nonsurgical sports medicine. Some people say orthopaedic surgeons make more money, but for me, it’s not about that. It’s about supporting patients in the best way I can.

Family medicine has a lot of female physicians, so I feel very comfortable there. Also, in AMSSM, one of my close friends, who’s a woman, is now the chair. Many board members are women too. That was another reason I was drawn to practicing family medicine in the U.S. I definitely feel supported. Even though our department chair is a man, he’s incredibly supportive of both men and women.

And I’ve noticed something more broadly in the U.S.—when a female physician is struggling, other women often step up to support her. That kind of solidarity happens more frequently here, not just in medicine, but in general. It’s one of the reasons I wanted my daughter to grow up in this kind of environment.