It’s the surgeon’s standard advice to patients as soon as they awaken from the procedure: start walking. Walk with help. Walk to the chair in your room. Walk as much as you can. But how many steps should patients actually aim for? One patient’s understanding of the instruction can differ from another’s, with a related impact on their recovery.

Researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center are looking to put a finer point on the matter with the help of wearable activity trackers. For a study whose results were published in JAMA Network Open, they outfitted 100 patients with digital step-counters and found that those who took 1,000 steps on day one post-surgery had 63% lower odds of a prolonged length of stay related to their operation. Steps counted above 1,000 did not have a similar association.

The AMA is committed to making technology an asset in the delivery of health care, not a burden. Efforts in this area include creation of the Digital Health Implementation Playbook to speed the adoption and scaling of innovative solutions.

Learn more about AMA’s transformative digital health efforts.

Back at Cedars-Sinai, researchers found that surgeons generally had a good idea of how well their patients were doing in their post-procedure ambulation, but the wearables revealed a wide range of step counts. Patients tabbed by surgeons as being “out of bed to chair,” for example, had a steps-counted range in the study of between zero and 1,800 steps.

In a JAMA Network Open commentary on the study, Stanford University surgeon Thomas M. Krummel, MD, cited Peter Drucker, PhD’s famous maxim that “if you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.”

“This article,” Dr. Krummel wrote, “demonstrates ambulatory status can be measured, thus raising the possibility of improvement.” Drucker, he added, “would be thrilled.”

The results with wearables at Cedars-Sinai prompted immediate work on a randomized-controlled trial, said the study’s lead author, Thomas J. Daskivich, MD, a surgical urologic oncologist who directs health services research for the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Department of Surgery. Dr. Daskivich also is associate professor of urology at Cedars-Sinai.

1,000 steps and an art education

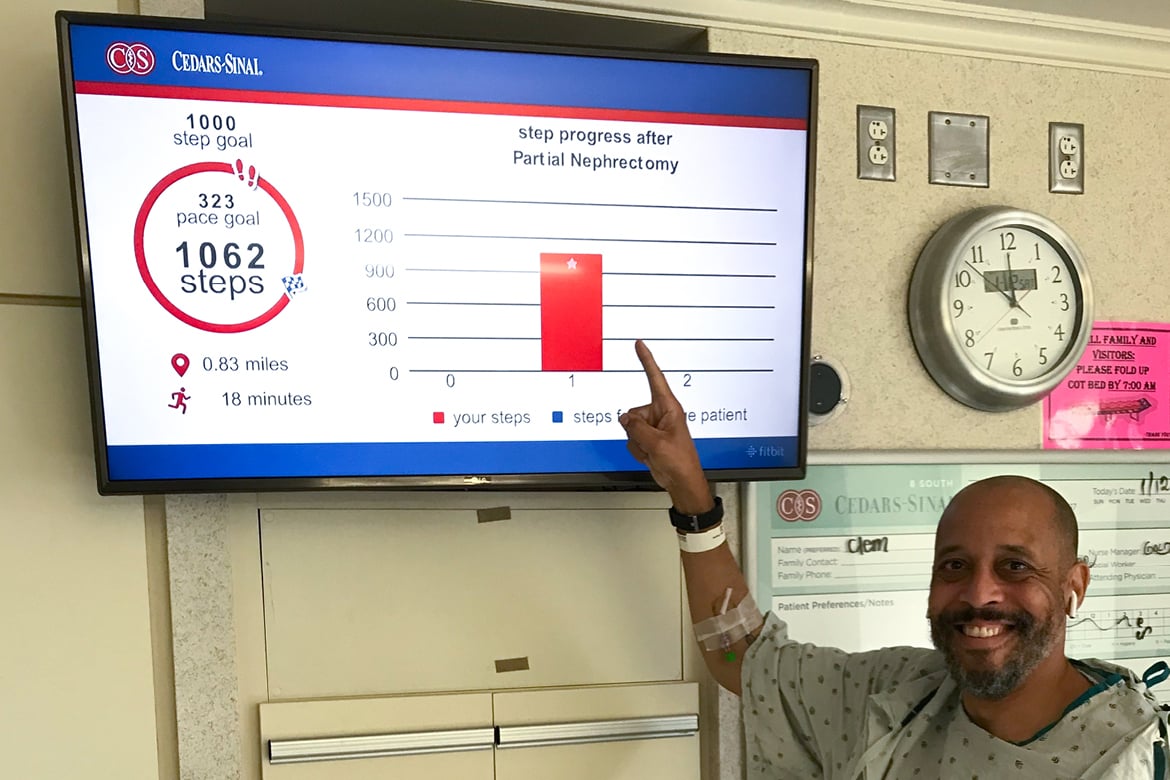

About one-third of patients for the trial have been enrolled. Using data from the wearables—made by Fitbit Inc.—a visual display of steps taken is available for patients to view in their rooms (as shown in the photo above). Patients in the trial also can use an app on their smartphones to take a guided walking tour of Cedars-Sinai’s museum-quality art collection. Those in the nonintervention arm will get the standard-of-care advice to walk soon and as much as possible.

“Every 100 steps toward the goal of 1,000 steps meant a 4% decreased odds of prolonged length of stay. Even that granular difference of half a lap around the unit was meaningful,” Dr. Daskivich said. “What we don’t know yet is whether giving patients feedback on step counts in real time toward their goal will motivate them to get to 1,000 steps a day.”

Anecdotally, Dr. Daskivich has found that giving patients a specific step-count goal can aid patient understanding and motivation. “A vague encouragement to walk as much as they can is not an actionable goal, and it has no endpoint,” he said.

Recently he encountered a patient who had taken virtually no steps or left bed after surgery. Dr. Daskivich showed the man how to use the in-room display to see his progress. When Dr. Daskivich returned three hours later, the patient had racked up 1,061 steps.

“I saw that there’s a goal there,” the patient said to Dr. Daskivich. “I saw how much I was doing, and I wanted to win the game.”

If the randomized-controlled trial is successful and future studies demonstrate a return on investment through shorter lengths of stay or fewer readmissions, then it wouldn’t surprise Dr. Daskivich to “see many major academic medical centers issuing activity monitors for all their patients after surgery.”